Chinese negotiators surprised their European Union counterparts this week with key market-access concessions—following long months of intransigence—that could allow the two parties to reach an agreement on a historic investment deal by year’s end.

Though EU officials haven’t yet revealed the details, one senior EU diplomat said the agreement goes beyond anything Beijing has offered any foreign partner previously, both in the level of market access and legal and other guarantees.

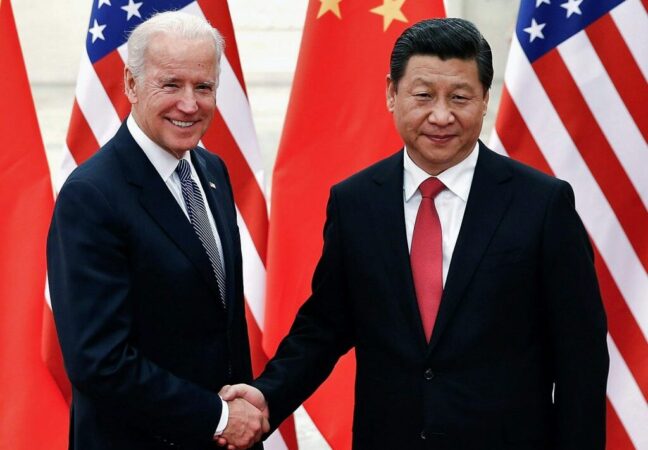

EU officials aren’t naïve about the deal’s historic timing or political significance. It would come shortly after Americans elected Joe Biden in early November, following a campaign during which he pledged to rally allies in Europe and Asia to work in common cause to counteract the unfair practices of China’s authoritarian capitalist system.

In Brussels, Beijing’s rush to close the investment agreement follows the European Commission’s proposal on December 2 to President-elect Biden for “a new transatlantic agenda for global change” that has at its heart nothing less than the ambition of bringing together Europe and the United States as a global alliance based on shared values and history.

EU officials I reached on Friday said they were torn between the opportunity to close one of the best investment agreements ever offered by China and the desire to seize the early days of the Biden administration to dramatically improve transatlantic relations. Should the EU close the deal with China, they are likely to argue to the Biden team that the concessions they gained from Beijing can also be applied to any future US agreements with China.

That said, President Xi’s underlying message to President-elect Biden, paraphrasing the Rolling Stones’ hit 1974 single, is that “Time Waits for No One.”

Xi isn’t willing to hit the pause button to provide President-elect Biden time and space to assemble his China team, reach out to allies, and frame his strategy. He won’t do so on trade and investment, nor will he do so in his efforts to crack down on political dissent at home. He is moving rapidly to gain greater self-sufficiency in developing key technologies, particularly semiconductors. And he will head off any efforts that would impede his ambition to unify Taiwan with the mainland during his leadership.

It’s clear that President Xi regards 2021, the centenary of the Chinese Communist Party, as perhaps the most important year since he came to power in 2013. He regards the decade ahead as decisive.

Nothing could have made President Xi’s personal ambitions clearer than the Fifth Plenum of the Central Chinese Committee, which concluded on October 29, just five days ahead of the US election.

“Judging by the Plenum’s outcome, Xi’s political ambition to remain in power for the next 15 years looks increasingly secure,” said Kevin Rudd, the former Australian prime minister, in a must-read speech as president of the Asia Society Policy Institute. Rudd sees the 2020s as the “make-or-break decade for the future of Chinese and American power.”

President Xi’s rush to close the EU investment deal is just one among many elements of his evolving, pre-emptive approach toward the United States in general and President-elect Biden more specifically, with elements that range from trade initiatives around the world to escalating actions against pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong and real or perceived dissidents at home.

Seen most charitably, President Xi is hoping to incentivize the Biden administration to more cooperatively negotiate similar agreements with Beijing. It had been a long-desired Chinese goal, before the decline of relations during the Trump administration, to achieve a so-called BIT—or Bilateral Investment Treaty—with the United States akin to what is being negotiated with the EU.

Seen less generously, Xi is boxing in the Biden administration long before the January 20 inauguration by locking its closest democratic allies into investment and trade agreements to which Washington isn’t party. Regarding human-rights issues—including this week’s arrest of a Bloomberg journalist and the jailing of newspaper founder Jimmy Lai and other Hong Kong democracy activists—he’s signaling that today’s China will resist President-elect Biden’s expected efforts to highlight human-rights issues.

President Xi is not only leveraging the long-standing commercial attractions of his country’s nearly 1.4 billion consumers. He’s also profiting from China’s significant success at getting COVID-19 under control. That, in turn, will allow China to be the world’s only major economy to post growth this year, at some 1.5 to 2 percent, with a shot at double-digit growth next year.

The news from Brussels follows last month’s announcement that 15 member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and regional partners—including China, but not the United States—had signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, or RCEP, one of the largest free-trade agreements in history. It is the first time China has come together with US allies South Korea and Japan in such an agreement.

Beyond that, President Xi has expressed interest in joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. The agreement was negotiated with the United States during the Obama administration, but President Trump pulled out of the talks, long before their 2018 successful conclusion, as one of his first acts in office.

For all his determination to reinvigorate relations with allies, President-elect Biden has said trade agreements won’t be a priority. There remains an insufficient constituency for them among Republican or Democratic lawmakers.

As always, it would be mistaken to underestimate China’s challenges, and they are many.

Among them are doubts about the Chinese economic model, particularly as President Xi tightens his controls over the private sector, including the recent blocking of the ANT initial public offering. China’s return to growth this year has been driven mostly by the state.

There are increasing signs that President Xi’s most ambitious international effort, the Belt and Road Initiative, is in trouble. Chinese officials are quietly reigning in its ambitions—and they face pressure to reschedule or forgive debts owed by poorer country partners.

It’s also not clear whether national self-sufficiency efforts will close remaining technology gaps, particularly when it comes to semiconductors. The Trump administration heightened tensions this week, putting China’s biggest chip maker and drone maker on an export blacklist, requiring US companies to get licenses to sell to them.

Whatever problems President Xi may have, he emerges from 2020 stronger than anyone anticipated when the coronavirus broke out in Wuhan late last year. In President-elect Biden’s inaugural year, it may be President Xi’s actions that are most worth watching.

-----

This article originally appeared on CNBC.com

Frederick Kempe is president and chief executive officer of the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @FredKempe.

The original article can be found @AtlanticCouncil

Leave a Reply