The World Health Organization has made it official: Coronavirus is the first “global health emergency” of our new era of major power competition. Thus, its ripples won’t stop at global markets but will also reach geopolitics.

It’s already clear that the coronavirus impact, though too early to fully measure, will be significant on Chinese and global supply chains, markets and economies; on the legitimacy and the trust enjoyed by the Chinese Communist Party with its own people; and on Asian regional politics and US-Chinese relations, where trust already was in such short supply.

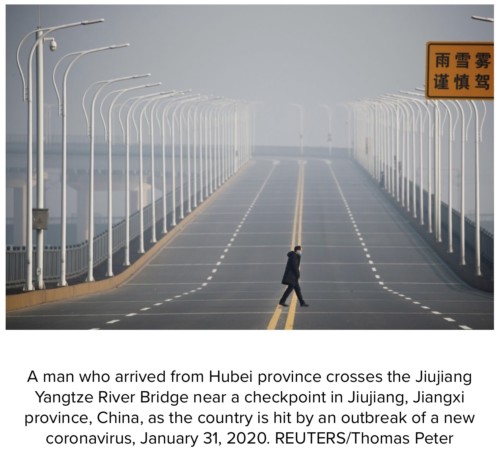

So, it’s not too early to contemplate the potential, unintended consequences of the virus, thought to have originated in a Wuhan wildlife wet market yet already having resultedin more than 210 deaths and more than 250 deaths and nearly 12,000 confirmed cases in all regions of China and 21 countries around the world. The cases now include the first person-to-person transmission in the United States, and a rare, new State Department level four advisory of “do not travel” to anywhere in China.

So even in a heavy news week during which the United Kingdom left the European Union, the United States announced a new Mideast peace plan, and the Senate advanced its impeachment trial of President Trump, none of that beats the potential of coronavirus for global impact.

Get the Inflection Points newsletter

The impact is all the greater as it coincides with what was already a slowing Chinese economy. It comes at a time when American and other companies were already shifting supply lines from China to elsewhere due to new tariffs and trade tensions. The virus will serve as another reminder for companies to more rapidly diversify their supply chains.

Following the Phase One trade deal with the United States, the coronavirus hit also undermines the whiff of bilateral trade optimism that had buoyed markets. It has quickly changed the narrative and increased the odds of a global market downturn in 2020. That’s particularly true among emerging markets and investments in commodities from oil to copper, both down double-digits.

Should the crisis stretch out for another month, and experts now consider it more likely than not to reach well into summer, the cost could be a two-percentage point decline in Chinese growth to 4% or lower this year. First quarter growth figures in China could fall to 2% year-on-year – which would be the lowest in decades, and down from 6% in the last quarter of 2019.

The impact on the global economy will be far more significant than during the SARS pandemic of 2003, which is estimated to have provoked a global economic loss of $40 billion and a hit of 0.1% on global GDP. That’s because China’s share of global GDP has quadrupled since then to 16% from 4% – and fully a third of global growth has been coming from China.

Tourism markets will take an outsized hit, as about 163 million Chinese tourists in 2018 accounted for nearly a third of travel retail sales worldwide. Thailand, for example, has already reduced its 2020 GDP forecast, based on expected revenue losses of as much as $1.6 billion from 2 million fewer Chinese visitors, should travel restrictions continue for a further three months.

More difficult to calculate will be the impact of the virus on Chinese President Xi Jinping’s legitimacy and that of his Communist party.

Wall Street Journal columnist Daniel Henninger referred to a rare public apology by Wuhan’s mayor Zhou Xianwang as “an epitaph” for the People’s Republic of China. “As a local government official,” said the mayor in explaining his slow response, “after I get this kind of information I still have to wait for authorization before I can release it.”

Wrote Andy Xie in the South Morning Post: “Wuhan’s failure shows up the systemic weaknesses in the top-down structure of the China model, where everyone in the hierarchy is accountable to someone above.”

“Though the economy will bounce back when the virus fades,” writes The Economist, “the reputation of the Communist party and even of Xi Jinping may be more lastingly affected. The party claims that, armed with science, it is more efficient at governing than democracies. The heavy-handed failure to contain the virus suggests otherwise.”

That brings one to the hardest impacts to calculate of all, and that is the geopolitics of coronavirus.

What’s known is that Chinese leaders’ confidence in their own rise, and the competitiveness of their alternative authoritarian capitalist economic model grew enormously during and in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008 and 2009.

Could the coronavirus have the reverse impact? The virus may or may not be overblown as a pandemic threat, but President Xi’s legitimacy in any case will be tested in his handling of the emergency, given how much power has been concentrated in his own hands. Conversely, his authority could grow if he’s perceived at handling the crisis well.

Meanwhile, the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab this week spotted what might be a sneak preview of how the global finger-pointing might shift through disinformation should the crisis deepen.

Several narratives have spread first on extreme Russian nationalist sites and to the Chinese internet, blaming the U.S. for the coronavirus outbreak. They’ve now been amplified by the Russian mainstream publications Pravda and Izvestiya. It’s reminiscent of Operation Infektion, when Russian propaganda during the Cold War tried to pin the spread of the AIDS virus on the United States.

At the same time, The Washington Times quoted a former Israeli military intelligence officer, who has studied Chinese biological warfare, that the coronavirus may have originated in an advanced virus research laboratory in Wuhan.

Mercifully, Chinese authorities are taking full responsibility thus far, although without being definitive about the virus’ origins, and U.S. officials thus far have praised the efforts.

That said, this is a story in its first stages. How it unfolds will help shape the contours of our age.

This article originally appeared on CNBC.com

Frederick Kempe is president and chief executive officer of the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @FredKempe.

Leave a Reply