The Federal Security Service (FSB) is one of Russia’s most closed government agencies, its work cloaked in myths and rumors. This secrecy makes it extremely difficult for outsiders to get a full picture of how the organization is structured and what it does.

The purpose of this report is to investigate the work of the FSB, assess the degree of its influence on the country’s politics and economy, and study the systemic problems it faces. Over the course of a year, the Dossier Center collected information about the structure, personalities, working methods, and main development stages of the FSB through careful study of open sources, databases, documents, criminal and civil cases, photo evidence, and audio recordings. The center also interviewed several dozen experts, including direct participants in the events described; former and current officers of the FSB, the Foreign Intelligence Service, the defense and interior ministries, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) Committee for State Security (KGB), and other government agencies; representatives of the business and the banking industries; eyewitnesses, victims, prosecutors, and defendants in cases involving the FSB; participants in illegal operations controlled by the FSB; and many others. The information obtained was also cross-checked and compared with data from other sources.

The report traces the history of the special services since Soviet times, which helps illustrate the institutional similarities and differences between the FSB and its predecessors. It also describes the internal structure of the special services based on verifiable data, though full information about departments, services, and employees is not publicly available.

The legitimate side of the FSB’s activities (e.g., counterterrorism and foreign intelligence tasks that are commonly regarded as necessary and justified) is not the subject of this report, and it will not disclose information that could harm the fulfillment of the FSB’s constitutional functions.

The influence of the FSB in political and economic spheres goes beyond the constitutional powers granted to the special services.

The president of Russia, to whom the FSB is directly subordinate, directs it not only through the agency’s leader, Alexander Bortnikov, but also through representatives of various units within the special services. Thus, there exists a multilevel FSB control system.

The president increasingly relies on information received from the FSB. Members of the special services with direct access to the president often use the organization for their own financial and bureaucratic purposes.

Members of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s inner circle hold sway over various parts of the FSB. Figures such as Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev,1 Rosneft Chief Executive Officer Igor Sechin,2 Rostec Chief Executive Officer Sergei Chemezov,3 Gazprom Chairman Viktor Zubkov,4 and former Security Council member Sergei Ivanov5 form groups of personal allies within the special services in order to advance their own economic interests, provide security, and share amongst themselves information useful to solving their own problems.

Over the past ten years, the FSB has taken control of many state institutions, usually by force or connivance. The defense and interior ministries, the Investigative Committee, the General Prosecutor’s Office, and other agencies have become dependent on the FSB. Members of the special services also regularly influence judges’ decisions. This power imbalance among government departments threatens the country’s security.

The FSB’s methods often violate the constitutional rights of citizens and still utilize some of the KGB’s worst practices. Officers of the special services and employees of other government departments dependent on them torture people, violate the freedom of speech, falsify criminal cases, raid and seize private businesses without justification, and participate in the murders of those, both in Russia and abroad, who run afoul of the Kremlin.

Representatives of the FSB systematically participate in corrupt schemes, including frequently organizing illegal financial dealings, especially in the banking industry. The FSB directly controls almost all illegal banking operations in Russia, at great profit to specific groups of FSB employees and representatives of their “clans.”

The FSB is also rife with ad hoc, opportunistic corruption, as low- and mid-level officers follow the leads of their superiors and use their positions to earn illicit income.

The FSB is a tool of repression against opposition-minded citizens and businesspeople who find themselves on the wrong side of the Kremlin, individual officials, or informal “clans.”

----

This report describes the transformation of the FSB from a state organization charged with safeguarding the public into a quasi-criminal body that has taken on the functions of a “second government” and invades all spheres of public and private life.

The first section of the report summarizes the organization’s internal dynamics and external influence, and traces the FSB’s evolution into a “special” service. The second section of the report is devoted to the structure of the FSB. It examines the activities and development of individual units, relying mainly on examples of high-profile cases involving the special services.

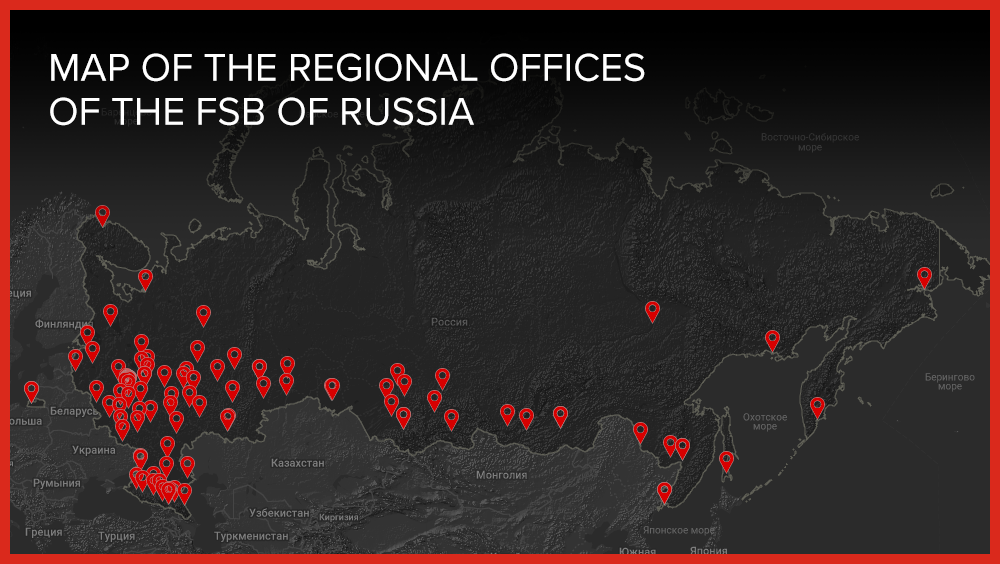

Map of the regional offices of the FSB of Russia. Compiled by the Dossier Center.

I. The FSB as a threat to the development of society

Contemporary Russia is a less repressive place than the USSR, not only during the Great Terror but also during the period of late stagnation. Nevertheless, the FSB is increasingly wielded as a tool for managing domestic policy, and the change has occurred so rapidly that it poses serious threats to society.

The danger comes from the FSB’s transformation into not only a political instrument of the Kremlin but also an unchecked locus of political decision making that is more powerful than, and unaccountable to, other state agencies. The longer other critical agencies stay sidelined, the harder it will be for the broader system to recover in the event of a governmental collapse, as happened in 1953 after former Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin’s death and could happen again when Russia undergoes its next change in leadership. A regime change would pose serious threats to various powerful groups within the FSB and could have unpredictable consequences, including elite attempts to usurp power by force or even a “civil war” among clans.

The combination of a lower degree of repression and the omnipotence of the FSB in modern Russia has two consequences:

- It leads Russia’s historical development into a dead end, since governing the country by way of loyal security officials is possible only as long as the guarantor of this system lives. When the guarantor dies, the country could enter a state of clan fragmentation, from which it would be extremely difficult to extricate itself peacefully.

- It prevents the normal functioning of not only a competitive economy but also a command and administrative economy (like that of the USSR). Without healthy competition, key business positions often go to those who cannot or will not make rational and competent decisions.

The combination of these factors leads to decline and stagnation in all spheres of Russia’s public life.

The history of Russia’s modern intelligence services begins on December 20, 1917, with the Bolsheviks’ creation of the Temporary Extraordinary Commission (VChK), a specialized body of political terror that was quickly put to work neutralizing political opponents during the revolution and the civil war. Throughout Soviet history, this organization repeatedly changed its name and function, but whatever the iteration—the Cheka, the State Political Directorate (GPU), the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU), the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD), the Ministry of State Security (MGB), or the KGB—it was always a repressive tool that sought to merge law enforcement into a single entity while maintaining its own isolation and unique power. This dynamic was plainly captured in 2002 by Nikolai Patrushev, then director of the FSB, who said the “State security bodies have always been an instrument of supreme power, of the existing political regime.”6 Patrushev made clear a dynamic that had long been at play—regardless of the Russian security and intelligence services’ official tasks, they were a malleable tool that could be deployed by those in power.

Meeting of the Cheka Board, 1919 (from left to right) – 1st – S.A. Messing, 2nd – Ya.H. Peters, 3rd unknown, 4th – I.S. Unshlikht, 5th – A. Ya.Belenky, 6th – F.E. Dzerzhinsky, 7th – G.G. Yagoda, 8th – V.R. Menzhinsky, 9th – G.I. Boky, 10th – G.I. Blagonravov, 11th – A. Kh. Artuzov, 12th – unknown, 13th – unknown. III. All-Russian conference of the Cheka. Credit: Wikimeadia Commons

An attempt to rein in and reform the KGB

The KGB was an integral part of the Soviet system built around communist ideology and its disintegration within a few weeks of the collapse of the USSR left behind a vast bureaucracy. Its employees went to work and, by habit, followed the instructions of their new leaders, but it was hardly the same KGB. Prior to 1991, the agency employed about 480,000 people, of whom about 260,000 were agents. When the Soviet Union fell, nearly half of the KGB’s staff was laid off, and the budget of the service was slashed.

A failed coup in August 1991 offered a chance to break the power of the KGB. Immediately after the coup, a commission led by Sergei Stepashin, then chairman of the Defense and Security Committee of the Supreme Soviet of Russia and a member of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of Russia, concluded that the agency was overly centralized and held control over all aspects of society without any legal basis and thus had become an independent political force.7

The last chairman of the KGB, Vadim Bakatin, presented seven actions and principles in his memoirs that would have to be pursued if the KGB were to be reformed:

- The KGB should be divided into independent agencies that would compete with one another as equals.

- Each union republic should have its own independent security service.

- The security services should comply with the rule of law and respect human rights.

- The security services’ work should not be guided by ideology.

- The services’ main focus should be on external criminal activity and domestic organized crime.

- The services should be as transparent as possible.

- The services must safeguard national security.8

Today, the FSB has, to a considerable extent, become the KGB incarnate.”

The headquarters of the FSB at Lubyanka Square also served as the headquarters for the KGB and its predecessors since the Cheka. Credit: Wikimeadia Commons

Russian President Boris Yeltsin made a serious attempt to implement Bakatin’s program. On August 30, 1991, a major reform meant to depoliticize the KGB was announced. Several independent state services were created from the previously unified “super-departmental agency”: the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), the Federal Protective Service, and the Federal Agency for Government Communications and Information. The purely political police directorates were abolished and the remains of the KGB were merged into an organization that was renamed several times before before the adoption of its current name: the Federal Security Service of Russia.

Today, the FSB has, to a considerable extent, become the KGB incarnate.

There are some key differences. The FSB performs different tasks, uses different tools, and offers different opportunities for corruption than the KGB, and instead of upholding communist or other societal ideals, it seeks to preserve the president’s personal power. It carries out targeted repression, but not mass repression. And, unlike the KGB, it can intervene in the economy at great profit to itself.

Yet the FSB inherited the KGB’s infrastructure, archives, agents, and more. Many former KGB functionaries had a hand in the formation of the FSB, and many moved to the new agency. Thus, through inheritance, Russia’s FSB has preserved much of the KGB’s ideology, skillset, and approach to operational work, and internal understanding of the role of intelligence officers.

Initially, FSB leadership proclaimed a break with the organs of Soviet state security and particularly disavowed crimes committed by the KGB’s Stalin-era predecessor, the NKVD.

“I emphasize that the FSB of Russia is not the KGB today,” FSB Director Nikolai Patrushev told Literaturnaya Gazeta in 2002.9 “This is a new domestic intelligence service corresponding to the new democratic form of Russian statehood. The basis of its activities is the protection of the law, nonpartisanship, and service to national interests.”

Over time, however, FSB officers began to identify increasingly with their predecessors, viewing the FSB as a true descendent of the Cheka. In fact, monuments to Cheka founder Felix Dzerzhinsky are regularly erected in its regional departments to this day.

Like the FSB, the main task of the KGB was to protect the regime from foreign and domestic political threats. But, unlike the FSB, the KGB was under some level of control from the ruling Communist Party. One of the paradoxes of the revolutionary changes of 1990 and 1991 was that as the party lost oversight of the state security organs, those agencies became a greater potential threat to the democratic foundations of the state. The prosecutorial oversight that replaced the party’s role was inadequate, and no effective mechanisms of parliamentary and public control over the special services arose in the 1990s.

It did not take long before old KGB forces tried to recover their former powers, albeit incrementally. It did not help that, instead of abolishing the old state security organs altogether and creating fundamentally new Russian special services under the control of parliament and civil society, the country’s leadership took half-measures to break up the KGB. As early as the first months of the independent Russian Federation, the highest posts in its special services were taken by officers from the Soviet KGB and the Interior Ministry, who in time demonstrated their loyalty to the president.

Monument to F.E.Dzerzhinsky: Lenin Street, 42, Ufa, Bashkortostan. Another statue, “Iron Felix,” used to loom from the center of Lubyanka Square, but it was torn down in 1991. In 2012, Moscow authorities stated that they intended to resurrect the monument. Credit: Wikimeadia Commons

And even as Soviet-era ministries and departments—including airline group Aeroflot, the media, large universities, the Intourist travel agency, and foreign trade organizations—were renamed, restructured, and variously privatized, KGB employees remained a secondary priority to reformers.

In January 1992, the Yeltsin administration attempted to create a Ministry of Security and Internal Affairs as a single “super department” in the face of socioeconomic chaos and the outbreak of a conflict with the Supreme Soviet, the national parliament.

This state of affairs is described by one of the Dossier Center’s anonymous sources, hereafter referred to as “S.” For context, this source served in the KGB’s First Main Directorate (foreign intelligence), and was sent as an “illegal” to the United States, where he was to find work, assimilate, and would not return to Russia for at least five years. Contact with his superiors was conducted in messages routed by the command structure for the “illegals” program, utilizing methods such as radio and coded announcements. Meetings with handlers were held in Mexico or Canada. After the collapse of the USSR, the employee received only a short message that the situation was unclear and there should be no contact until further notice. Then silence followed. Only after a year and a half was he invited to meet with a handler in a neighboring country. They met, but no new instructions were received, except to continue work. In the mid-1990s, SVR representatives called the agent home.

The source told the Dossier Center that KGB agents were true believers, convinced that certain other countries posed a threat to the existence of the USSR. Also notably, he said, upon his return to Russia in the 1990s, he saw a marked decline in the professionalism and discipline of intelligence officers, who, for example, would transfer documents with virtually no thought to proper tradecraft.

The source also reported a generational conflict in the modern FSB. Young people come to the service seeking to earn money, but veteran employees hinder them in order to maintain their monopoly on grafting schemes. Intelligence and security officials have tried to reimbue the work with an ideological component by, for example, creating the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (RISI) at the Foreign Intelligence Service. These attempts have been, however, largely unsuccessful.

RISI was established in February 1992 as part of the KGB’s Research Institute of Intelligence Problems.10 In 2009, it was transferred to the presidential administration under retired SVR Lieutenant General Leonid Reshetnikov. As former employee Alexander Sytin told Radio Liberty, Reshetnikov previously worked in the First Main Directorate of the KGB and at some point became obsessed with the “White Movement, the White Orthodox idea, and the spiritual and territorial revival of the empire,” all of which are ideas stemming from the anti-Bolshevik “Whites”—forces fighting against the “Reds” in the Russian Civil War.11 Sytin said “the main business” of Reshetnikov’s life was placing the work of the Russian intelligence services in the same far-reaching historical pantheon of anti-Western Russian warriors. “His passion gradually captured the institution subordinate to him. Its main idea was anti-Westernism,” Sytin said.12

Later, the presidential administration created the Center for Humanitarian Research, which was designed to reverse what it called the falsification of Russian history. One of its leaders was Peter Multatuli, a former Interior Ministry official who sought to revive the “sacred memory of the martyr king.”13 In turn, Ukraine expert Tamara Guzenkova was appointed to lead the Center for the Study of Problems of the Near Abroad Countries. Together they promoted anti-Ukrainian ideas, calling the country “Little Russia” and “the result of the criminal destruction of the Russian Empire by the Bolsheviks.”14In November 2016, RISI’s status got a boost when former SVR Director Mikhail Fradkov was chosen to lead it. And in 2017, Reuters reported that RISI had developed proposals to ensure the victory of Donald Trump in the US presidential election.15

FSB and Soviet KGB: Differences

Although it might seem that the contemporary FSB would attract people with certain worldviews, employees’ ideologies are their own business and the FSB has no official creed.

Also unlike the Soviet-era VChK, OGPU, and NKVD, which recruited according to Marxist ideas of class and where officers of the previous tsarist secret police were rarely found, the FSB is largely composed of former KGB officers. Additionally, it inherited many aspects of the KGB, including structures, operational methods, and archives. As such, it is an organization largely composed of those dedicated to enforcing the will of the previous regime, now tasked with imposing the will of the current regime.

Most fundamentally, the FSB and the KGB differ in their natures and functions as institutions of power. They play different sociopolitical roles and wield differing degrees of influence on society and the state. The KGB was part of a broader “repressive whole,” an element of the system created by the Bolsheviks, as well as one of many tools, albeit an important one, to ensure the survival of a communist state.

The FSB, which has fallen out of the “ideological field,” has itself become a backbone of the system, a new and fundamental point of support for the authorities. The story of the FSB, though, is not one of perfecting the tools of party ideological terror, but rather of the emergence of an independent agency to implement and sometimes make strategic political and economic decisions.

Commercialization of the FSB

The formation of this fundamentally new political force, which took place throughout the 1990s and continued until 2003, happened in three stages: commercialization, criminalization, and emancipation. Commercialization and criminalization, which took place virtually simultaneously, were the inevitable consequences of the de-ideologization of the service during the protracted general political and economic crisis of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Emancipation occurred later and testified to the completion of the organization’s rebirth and its attainment of a new level of influence.

Amid the chaos of the Soviet Union’s collapse, tens of thousands of officers in the Russian special services lost the stability of a reliable living wage—the state, which was in deep economic crisis in the early 1990s, often could not pay members of the security forces enough to keep them satisfied. Under these conditions, when officers were not given enough to remain honest and operate with integrity, the temptation to exert pressure and use violence for personal gain was extremely high. Along with carrying out their core mission, members of the special services began to look for additional sources of income where they could.

These security service officers started looking at exactly the right time. Newly legalized private businesses urgently needed protection from rampant criminality in a rapidly changing “Wild East,” and they now had the capital to pay for it. Thus began the massive and uncontrolled commercialization of the special services, in which members used their connections, skills, and official powers to make money on the side.

In this state of dual loyalty, these officials quickly learned to serve both the interests of the state and their personal interest in aquiring private capital. In this, special services officers were not much different from employees of other law enforcement agencies, including police officers, prosecutors, and customs officers. The Russian security services were, in a way, lowered—no longer in the sole service of a major power, but also in bed with cutthroat business.

The privileged criminalization of the FSB and “Gangland Petersburg”

Business security was not the only opportunity that awaited underemployed KGB agents in the early 1990s. In the ashes of the Soviet Union, a slew of organized crime groups rose up, and the authorities lacked the resources to stop them. These gangs stole, trafficked in arms and drugs, and “protected” businesspeople for a certain percentage of their profits. KGB officers familiar with both the basics of conspiracy and security service methods proved especially useful for that type of work. Working directly in the sphere of organized crime, intelligence officers could count on decent earnings and help in resolving personal issues. They often cited operational reasons to justify their cooperation with criminals, effectively legalizing this activity.

Although this union of crooks and security forces took place almost everywhere, its development in St. Petersburg would have huge implications for contemporary Russia. In that city, regional FSB employees, city bureaucrats, and top gangsters formed a lasting criminal coalition that resulted in the emergence of systemic and systematic corruption with international ties that was unprecedented for Russia and more akin to the heyday of the Italian mafia or American crime syndicates during the Great Depression.

At the nexus of the three groups that made up this illicit coalition was an official of the St. Petersburg city government, Vladimir Putin. As a top official in St. Petersburg’s government, Putin saw firsthand the magnitude of power that joining criminal and official elements in partnership could create. As a top intelligence chief, he would translate these lessons into action.

Anatoly Sobchak, a leading Soviet-era reformer and former mayor of St. Petersburg next to his mentee and then-Acting Russian President Vladimir Putin in 1994. Sobchak died in 2000 from a heart attack. Both of his bodyguards who were with him were supposedly treated for symptoms of poisoning following his heart attack. Credit: Reuters

After Putin was appointed head of the FSB in 1998, he restructured the special services, replacing top leadership with figures he knew from St. Petersburg and shaping the agency’s evolution over the turbulent years to come.

In short order, members of the St. Petersburg circle began to move to Moscow and take up other government posts, as well as positions in commercial and nonprofit organizations affiliated with the state.

With Putin at the FSB, the organization cemented its position at the center of the Russian political system, and this union of Chekists, officials, and criminals now had the ability to influence all spheres of the country’s operation. Still-fledgling civil and state institutions were no match for this threat, which even started to win popular support when spiking oil prices allowed the coalition to take control of massive cash flows and make well-received populist gestures. Corruption was pervasive, and it was the way things got done.

Emancipation and expansion of FSB functions

As the FSB changed, it sought to reclaim its perch atop not only the government but also the country’s business and economic operations. Even today, the FSB seeks to restore its status as a super-service that broadly surveils society and the state apparatus, as well as other less powerful security and justice organs. To that end, since the late 1990s, divisions have been created within the FSB that can go beyond strictly defined constitutional duties. For instance, they permit the control of other law enforcement agencies—the prosecutor’s office and, subsequently, the Investigative Committee, the Interior Ministry, customs, and the Federal Protective Service, among others. Perhaps the most important structural change of the 1990s was the creation of the FSB’s Department of Economic Security, or Department K, which gave the special services more scope to intervene in financial and business matters. In addition to counterintelligence and counterterrorism, the FSB could now control the economy. Gradually, it was once again becoming a superagency.

Among a new wave of structural changes in 2003 and 2004, as Putin consolidated his position as president, he transferred to the FSB the functions of the Federal Border Service and part of the Federal Agency for Government Communications and Information.16

Meanwhile, power struggles with other government departments continued, and the FSB shook up its relationships with criminal groups.

As organized crime soared in the 1990s, the Interior Ministry, through its Department of Combating Organized Crime, took the lead in related investigations. At the same time, FSB officers and criminals cooperated in more or less a balance of power, with the scales probably tipped slightly in favor of the gangsters. As Putin’s appointees took up nearly every critical post within the FSB in the early 2000s, however, the security service began to hold greater sway. Although “working” cooperation continued, organized crime was subordinated to the FSB.

The agency also elbowed aside competition from the Interior Ministry when the ministry’s regional departments were made subordinate to headquarters in Moscow. As a result, the police interfered less with local FSB officers and conflicts were resolved through the federal center. In the early 2000s, the Interior Ministry’s organized crime department was sidelined, and in 2008 it was abolished.17

The FSB and the other security ministries

In 2004, Putin gave special services leadership much broader powers.18 In particular, the director of the FSB could determine the membership and size of the agency’s governing board19—even the KGB had had to accept a board whose members were approved by the Council of Ministers and the Communist Party’s Central Committee.20

By the same 2004 decree, the number of deputy directors was slashed from twelve to four, and some departments, which until then acted as independent units, were abolished. Instead, independent services were created, within which departments were formed—effectively spreading and decentralizing zones of control.21According to a public comment by Colonel-General Yevgeniy Lovyrev, head of the FSB’s Department of Organizational and Personnel Work, the leadership of the FSB had a leading hand in the decree. Putin’s decree made the FSB a state in a state, a virtually self-governing structure. The powers of the special services expanded significantly beyond those enumerated in the constitution: From that moment, the FSB could intervene in any situation, not just those related to domestic counterintelligence. Moreover, what little external oversight of the FSB that existed was scaled back.

President Vladimir Putin meets with Igor Sechin, now the CEO of Rosneft, Russia’s largest oil company, in 2019. He created the “Sechin Special Forces,” officially the Sixth FSB Office of Internal Security Management. Credit: Office of the President of Russia

In 2004 and 2005, Igor Sechin, a friend of Putin’s who held the offices of deputy prime minister and deputy head of the presidential administration, created the Sixth FSB Office of Internal Security Management (the so-called “Sechin Special Forces”), one of the agency’s most influential units. According to a former FSB officer, the Sixth Service was created primarily to expand the scope of FSB operations, which were traditionally more limited than the Interior Ministry’s, despite the intelligence agency’s greater access to information.22

The FSB investigative apparatus technically had a relatively narrow jurisdiction, with which its Moscow representative office, in contrast to its regional ones, strictly complied. This jurisdiction did not include, for example, economic affairs. The Sixth Service was created in part to compensate for this conservatism and lack of efficiency in competition with the Interior Ministry. Two main goals of the new service were finally liquidating the Interior Ministry’s organized crime directorate, which in the mid-1990s repeatedly detained FSB officers during raids, and undercutting the Interior Ministry as a whole. The new service was conceived as a “superstructure” over other inter-governmental competitors, as the operational body to which the most promising candidates were recruited.23

Sechin’s hold on the office allowed the FSB to branch out once again beyond the limits originally conceived and in proportion to the internal counterintelligence body. It also allowed Sechin to use the unit for his own economic interests. The Sixth Service was especially useful because it was able to influence other FSB departments and organs.

The Sixth Service is also in charge of witness protection, which it uses for both legitimate purposes and control over those who have attracted the malign interest of the FSB—be they criminals, targets, or political enemies. Thus, the office has become a way for its employees to make money: many businessmen, especially in the shadow economy, are willing to pay considerable sums for the services of the Sixth Service. For example, banker Yevgeniy Dvoskin, who helped gangsters and corrupt officials convert their illicit gains into cash, had long been under state protection in 2007 when Interior Ministry forces tried to arrest him.24 He reportedly escaped from the scene with FSB officers in a vehicle disguised as an ambulance.

Along with the other changes in 2004, the FSB’s intelligence directorate, which founded in 1999 and whose officers were allowed to travel abroad, was reorganized into the Department of Intelligence as part of the Fifth Service.25 The FSB Information Security Center was also created in the same sweeping vein.

A year earlier, the Federal Border Service had been abolished.26 Its functions and resources were transferred to the FSB Border Service, giving the FSB responsibility for all cross-border aviation security.

As a result of the changes of the 1990s and early 2000s, the FSB became much more powerful, especially in information-gathering and by taking advantage of opportunities to insert itself into spheres not within its original, reasonable mandate. The service had also become financially independent, as the creation of its own airline showed. All of this happened while external oversight of the special services was whittled away. As a result, the agency conceived by Yeltsin exclusively for counterintelligence purposes has become something more. A new structure in line with the service’s growing ambitions developed around 2007 and 2008.

As the FSB became an instrument in the hands of the ruling elite, the special services began to perform new functions defined not by laws, but by private understandings. These functions, which include safeguarding the economic and political interests of the ruling elite and carrying out political repression, have largely supplanted its constitutional mandate to ensure public and state security. The process of internal reform of the FSB, which began in the early 2000s, was finally completed from 2011 to 2014.

The Federal Security Service will never serve any party or group interests, but will do its work on the basis of the law and in the interests of the entire state.”

Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin (C) answers journalists’ questions as Interior Minister Vladimir Rushailo (L) and head of the domestic security service (FSB) Nikolai Patrushev (R) look on at a news conference after the meeting of the law-enforcement ministers of the Group of Eight nations in Moscow October 19, 1999. Putin vowed to halt the flow of dirty money from scandal-plagued Russia as he opened the conference. Source: Reuters

Economic lobbying

Economic or commercial “fixing” in this report refers to the use of FSB resources to redistribute markets (including illegal ones, such as smuggling or drug trafficking); seize, hold, and redistribute assets; and protect the economic interests of the well-connected.

The first major scandal that showed the public the depth of FSB involvement in commercial activities happened in 2000. In the “Three Whales” case, a few top-level FSB officers close to Putin were caught importing furniture from China without paying customs fees or taxes.28 Ultimately, the president himself intervened, and none of the main defendants was punished. Investigators and prosecutors put the case on hold, and only secondary actors were held responsible in the end.

Five years after the Three Whales, FSB officers were caught using property owned by their department as a way station for Chinese goods smuggled into the country. The scandal led to some top-level resignations, but the accused were able to continue their careers in government and private industry. The case’s resolution signaled that the FSB had become untouchable, and it attracted groups and individuals who wanted to use its considerable resources to solve their own financial or extralegal issues.

As a result of the aforementioned cases, a significant blow was inflicted on the Federal Drug Control Service of the Russian Federation (FSKN). In October 2007, FSKN General Alexander Bulbov and several of his colleagues were arrested and charged with illegal wiretapping. A few days later, Bulbov’s boss, Viktor Cherkesov, wrote a column in Kommersant acknowledging the conflict between the FSB and the FSKN, as well as the commercialization of the special services.29 Putin was not pleased, telling reporters, “I consider it wrong to air such problems in the media. And if you’re going to do that, makes claims about a war between the special services, you yourself must first be beyond reproach.”30 Ultimately, Bulbov was sentenced in 2010 to three years’ probation.

In May 2008, after Dmitry Medvedev was elected president, Cherkesov was transferred from the Federal Drug Control Service to the Federal Agency for the Supply of Arms, Military, Special Equipment, and Materials.31 Two years later, he was fired. According to press reports at the time, the president could never forgive his longtime ally for airing dirty laundry in public.32 After Cherkesov’s departure, FSKN was led by Colonel-General Viktor Ivanov, who came from the St. Petersburg security officers’ clan. The new head of the drug-control service became known for showy public relations stunts and scandals.

Political operations

While the FSB took on its new economic functions, it also started to conduct political operations with the explicit or tacit consent of the president, his administration, and the Security Council.

In 1999, for example, the FSB was involved in the dismissal of Prosecutor General Yuri Skuratov, who a year earlier had investigated potential wrongdoing by Tatyana Dyachenko, daughter of Boris Yeltsin, and Deputy Prime Ministers Anatoly Chubais and Valery Serov.33 It was one of the earliest examples of the use of the FSB in clashes among the elite.

Russian First Deputy Prime Minister Boris Nemtsov (L) and Defence Minister Igor Sergeyev (R) reach out to shake hands as Deputy Prime Minister Valery Serov looks on during the government meeting, September 25, 1997. Nemtsov would later oppose Vladimir Putin’s government and was assassinated in 2015. Credit: Reuters

The episode started in 1998, when Skuratov launched an investigation into hundreds of government officials suspected of using their positions to profit off the short-term bond market. Among them, according to Skuratov, were Chubais, Serov, Dyachenko.34 That same year, Skuratov filed a lawsuit against the Yeltsin administration alleging an administration official had received roughly $60 million in kickbacks for awarding lucrative construction contracts.35 The case was investigated jointly with Swiss law enforcement agencies.

A few months later, a video appeared on the state TV channel showing a “person resembling Skuratov” in bed with two sex workers. After that, the FSB opened a criminal case against the prosecutor general for abuse of office and Skuratov was removed.36 Skuratov said the video was faked and called Putin the mastermind of the plot against him.37 In his 2012 book, Putin—The Executor of Ill Will, he wrote that Putin, at the time FSB chief, had pressured him to resign in order to avoid a lengthy dismissal process in parliament. For Putin, the Skuratov case was an opportunity to demonstrate loyalty to Yeltsin and his entourage.38

The takeovers of NTV, YUKOS, and Sergei Magnitsky

The FSB’s next audacious show of strength was its participation in the seizure of private television channel NTV in 2001.

NTV was majority-owned by Media-Most, a holding company formed by entrepreneur Vladimir Gusinsky. Known for its editorial independence, the channel had investigated a series of mysterious explosions in September 1999 in which the FSB was suspected of being involved.39. It had also opposed the Chechen War, probed official corruption, gave unsparing coverage to the Kursk submarine tragedy, and poked fun at officials on its Kukly satirical puppet show.

On May 11, 2000, employees of the Prosecutor General’s Office, the FSB, and the federal tax police searched the station’s offices, and two days later Gusinsky was arrested on fraud charges.40 Officials reportedly told Gusinsky he could go free and keep his other assets if he would sell his NTV shares to Gazprom.41 He agreed. The press reported that this condition was included in annexes to Gusinsky’s agreement with Gazprom, and the European Court of Human Rights subsequently cited it in their finding that his arrest had been politically motivated.42

Armed and masked men identifying themselves as tax police chat as they survey the entrance to the head office of the Media-Most group, on May 11, 2000. Credit: Reuters

NTV’s seizure set off a firestorm. Protesters held rallies and pickets in its defense, with some regional media claiming solidarity with the channel. Still, the station stayed in the hands of Gazprom’s media company. Many NTV journalists resigned and several of its marquis programs were canceled.

Putin made a show of staying above the fray, saying he did not feel “entitled to interfere in a dispute between business entities.”43

NTV’s capture was the first major case of the government using special services to put political pressure on the media.

The Yukos Affair

The FSB also played a major role in the expropriation of the Yukos oil company, which marked the start of political raiding of private companies in Russia. The beneficiaries of this operation, which began with a criminal case of tax evasion in 2003, were figures associated with the security forces and the president.44

In taking over Yukos and imprisoning its owner, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Putin’s team accomplished three important tasks: eliminating the threat to the president’s rule posed by Khodorkovsky, a funder of the opposition; strengthening its own bridgehead in a strategically important industry; and sending a warning to owners of other large businesses. The Yukos affair changed the nature of relations between the government and entrepreneurs in Russia: Now, business was allowed to own significant capital only in exchange for political loyalty and avoiding any criticism of the president.

Even though employees of various law enforcement agencies were involved, all of them acted with the authority of the FSB, which directed the operation.

The case of Sergei Magnitsky

A few years later, in 2007, police raided the offices of the highly successful investment fund Hermitage Capital, run by British financier William Browder.45. When the fund’s lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, discovered that figures in law enforcement were fraudulently claiming huge value-added tax (VAT) refunds in Hermitage’s name, using company stamps apparently pilfered during the raid, he was arrested and charged with tax evasion.46 Security officials demanded Magnitsky make a deal and testify against Browder. He held out, and after eleven months of imprisonment, Magnitsky died in jail, having allegedly been beaten and suffering from chronic health problems that investigators and judges ignored.47

The Magnitsky case was an operation of the FSB’s Economic Security Service. His death set off one of the largest international scandals in the history of post-communist Russia and led Browder to champion passage of the Magnitsky Act, mandating sanctions on Russian human rights abusers, in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom (UK), and other European countries.48Nevertheless, it served the purpose of putting foreign businesses in Russia on notice that they would not be treated differently from those that are domestic. Cooperating with the authorities, including handing over kickbacks and bribes, would be the cost of doing business there.

Dmitry Kratov, the former deputy head of the Butyrskaya prison where Magnitsky was held, was the only person being tried in connection with the death of Sergei Magnitsky. Here, he waits before a court session in Moscow on December 28, 2012. Kratov was later acquitted of the charge of negligence over the death of Sergei Magnitsky. Credit: Reuters

The FSB as “Shadow Government”

Today, the FSB has displaced a variety of state institutions and continues to exert behind-the-scenes control of every source of power in Russia. In addition to their direct duties, intelligence officers help resolve political and economic issues in the interests of Putin, his inner circle, or the president’s administration.

Given its preeminent role in running the country, the FSB has naturally become a battleground for power and resources. In a democratic society, political conflicts play out in the party system, the legislative branch, and lobby groups, while financial disputes are resolved through the judicial system. In contemporary Russia, these conflicts manifest as an interclan struggle for influence on and within the FSB.

Every financial-industrial group that matters has representatives inside the FSB, just as elsewhere they might have representatives in the legislature, government, or the courts. Today, special interests lobby the FSB just as much as they lobby the administration.

The special services’ priority remains the people from Putin’s inner circle who maintain their FSB clans, or officers who have the president’s ear. With his approval, these officers can target the leaders of various government agencies or major businesses using a wide range of methods from planting evidence to aggressive targeted encounters intent on provoking a desired crime. Sometimes, representatives of the special services ask for consent after an operation is already underway, as in the case of Denis Sugrobov, who led the Interior Ministry’s anti-corruption unit.49 Sugrobov’s team was targeted by the FSB and he was eventually convicted in 2017 on charges of organized crime and abuse of power.50 In such cases, the outcome depends on which of the warring parties is the first to reach the president with their version of events.

This system makes Putin the final arbiter while not allowing him to see things as they really are. To address this shortcoming, he has tried to develop something akin to checks and balances inside the special services by encouraging clan rivalry in the FSB and not allowing any particular group to amass too much power. For example, the former head of the FSB’s Sixth Service, Oleg Feoktistov, widely considered Sechin’s man, was balanced by Sergei Korolev, who formerly led the FSB’s Internal Security Department and belongs to a different clan.

The relationship between the FSB and the president of Russia

The FSB is Putin’s tool of choice among the country’s law enforcement and security agencies.

In general, the trend is toward a single-channel system of government supported by the FSB as other agencies, whether in the security realm or not, lose their influence. To date, conflicts with other state institutions have typically been resolved in favor of the FSB.

One after the other, the FSB has bested and often absorbed other security agencies, from undermining the first head of the State Drug Control Committee, Viktor Cherkesov, in 2007, to gaining operational control of the Customs Service under Andrei Belyaninov and the Federal Protective Service under Yevgeniy Murov. But the FSB established its full supremacy only recently. In the early 2010s, the Prosecutor General’s Office could effectively counter the agency and protect its employees from criminal prosecution when Moscow-area prosecutors were working illicitly with casinos, but that was essentially the last successful challenge by a state body to the FSB’s power.

From 2015 to 2017, the FSB showed itself to be Putin’s enforcer when the Sixth Service’s Internal Security Department (USB) detained three regional governors in criminal cases.51 Many political commentators speculated that the agency acted on its own, but the facts indicate that Putin pulled the strings. The governors’ arrests took place after months of painstaking preparations, and the orders came from above.

Vladimir Putin talks to the director of the Federal Security Service Alexander Bortnikov after a wreath laying ceremony to commemorate the beginning of the Great Patriotic War against Nazi Germany in 1941 at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Moscow June 22, 2012. Credit: Reuters

The FSB is the tool that Putin uses to redistribute local economic resources to favored clans, meet public demands to fight corruption, and ensure political loyalty from regional officials, a favorite tactic in Russian officialdom. Since the country’s economy depends on its relations with Western countries, Putin pays lip service to democracy, but Soviet-style purges have given way to carefully chosen, high-profile operations that pacify Russia’s “dissenters” and regional elites. In parallel, under the guise of the fight against corruption, a redistribution of wealth, resources, and market share occurs out of public view, to the benefit of those close to the Kremlin and the security forces.

Today, Putin is trying to consolidate his control over the FSB beyond the oversight he exercises via the administration and the Security Council. He seeks to establish regular communication not only with the agency’s director, Alexander Bortnikov, but also with the heads of directorates and departments. In doing so, he causes competition and friction between the formal leadership of the service and the subordinates who benefit from direct contact with the president.

The peculiarity of Putin’s status lies in the fact that he both runs the FSB and is its main client. He is the dominant force in the relationship: If he has clearly expressed his firm opinion on some issue, he can almost always impose his will via the FSB. Yet, because the FSB has eclipsed other security agencies, the president is increasingly dependent on its information and counsel to form his opinions, so the tail wags the dog.

Increasingly, the outcome of corporate conflicts depends on who made the first report to government authorities, which has led to a rapid wounding of rule of law within the Russian system. This is an essential difference from the Stalinist system of personal power, as Stalin relied on both the party and the state security agencies, which he kept strictly separate, while Putin relies solely on the FSB.

Overall, the FSB has seized control of the entire law enforcement apparatus. It has so thoroughly eliminated or established primacy over competing security institutions that the only remaining oversight of the FSB is the personal control of the president, who tries to manage it via its director and those under him who carry out policy.

The FSB as a commercial and political exchange

The FSB’s altered role has led to an internal contradiction between its formal and informal structures. The formal structure of the service and its rigid hierarchy correspond to its declared constitutional functions. In parallel, the FSB also functions as a center for informal decision-making and implementation.

Lawyer Genrikh Padva (C) and former Russian Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov (in back seat, obscured) sit in a car as they arrive at the prosecutor’s office in Moscow January 11, 2013. Serdyukov was caught up in a case that snowballed into the biggest corruption scandal since President Vladimir Putin’s return to the Kremlin at the time. Credit: Reuters

In adapting to the new responsibilities and powers absorbed from other organs, the agency has changed organizationally and begun to resemble a collection of interest groups independent of the formal hierarchy. For example, Sergei Korolev, director of the FSB’s Economic Security Service, and Ivan Tkachev, chief of that service’s Department K, which oversees banks and other financial institutions, were at odds because they “belong” to different clans.52 Sometimes officers act in accordance with their formal positions, and sometimes with their informal allegiances, sowing confusion. The leaders of these informal groups may have influence comparable to, or even sometimes exceeding, the powers of the formal leaders of the FSB.

Relations among influence groups within the FSB and their clients—the corrupt businessmen, criminals, and political figures looking for an advantage—are fluid, with the “principal” and “agent” roles repeatedly changing to match the situation. Sometimes influence groups promote certain decisions in the interests of their clientele, and at other times they work to advance their own interests. In extreme cases, these groups can even turn on their clients. In general, influence groups are freelancing more, working simultaneously with different customers, maneuvering the landscape, and rapidly building up their own fiefdoms. Only clients who maintain direct access to the president remain privileged, but even that is sometimes not enough of a shield—a recent example being the case of former Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov, who was caught up in a wave of dismissals relating to an embezzlement scheme in the Defense Ministry, despite there being no accusations of embezzlement against him.53

With its unparalleled influence, the FSB can insert itself into any criminal investigation. To allow the agency to directly control investigations, as in the probe of Boris Nemtsov’s murder, officials sometimes set up long-term interdepartmental task forces. These groups can include investigators, supervising prosecutors, operational police officers, and members of the FSB, as well as other interested parties, such as members of longstanding, institutional law enforcement organizations, usually responsible for communicating with the criminal world.

The FSB can directly control any criminal investigation and turn it into an ineffectual window dressing established by legal relations among prosecutors, investigators, and judges. In other investigations, the FSB exerts influence unofficially, through seconded employees or covert agents. As criminal cases have become a primary tool of manual control of the state—the kind of weapon that can be deployed when the government wants direct influence and action—the FSB’s opinion has become decisive on almost any economic or political affair of interest to the special services.

II. How the FSB actually works

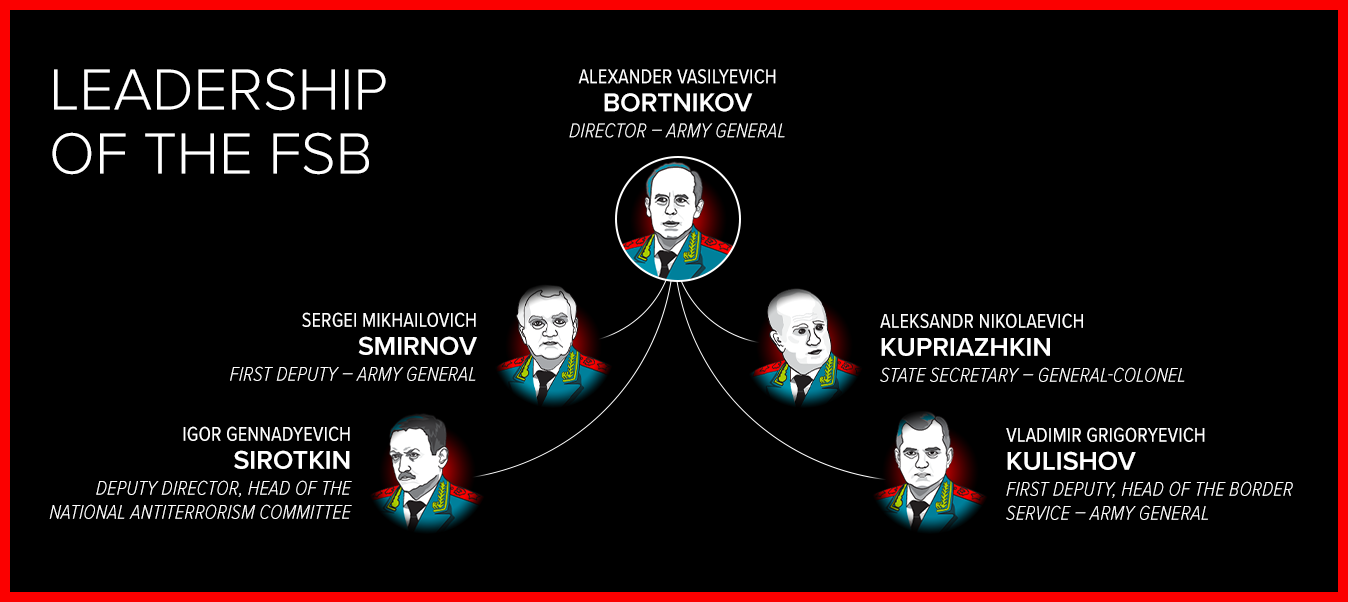

An organizational diagram of the key leaders of the FSB.

FSB involvement in economic crime

To better understand how the FSB works, it helps to look closely at some of the organization’s key departments. Among the most influential is the Fourth Service for Economic Security (SEB), including its counterintelligence department for the credit and financial industry, Department K.

Formally, the SEB is engaged in counterintelligence support of such strategically important areas as industry, transport, and communications. At the same time, SEB is responsible for the security and stability of the financial and banking systems.

These declared tasks are undoubtedly important, especially considering the risks inherent in a globalized economy and financial system. But control and regulation of the financial industry do not fall under the rubric of counterintelligence in any Western country, and they go far beyond the reasonable powers and competence of the special services—regulation of finance and banking would typically fall to the central bank and the Finance Ministry. In Russia, the SEB’s control over these institutions allows the agencies to intervene in purely economic processes, and the absence of external oversight allows the SEB to control, organize, and cover up illegal activities.

Money laundering, illegal financial transactions, and capital flight have reached unprecedented levels in Russia.

By one estimate, Danske Bank alone has laundered at least $230 billion dollars and Swedbank $149 billion dollars from Russia and other former Soviet countries.

Erichsen Mansion in Copenhagen, Denmark, serves as the headquarters for Danske Bank. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Excessive power breeds corruption at the SEB and other FSB services, the private banking system, and government institutions, including the central bank and the Deposit Insurance Agency (DIA). Personal enrichment is the primary goal. The corruption of the special services and their fecklessness in the fight against financial crimes undermine the Russian economy and the country’s credibility in the global market. Ultimately, the investment climate suffers and growth slows.

In the 2000s, a “state-criminal partnership” developed in Russia, in which the shadow financial services market was monopolized by the SEB/FSB under the leadership of current FSB Director Alexander Bortnikov. Since then, SEB employees control the entire chain, from schemes for withdrawing money from the budget to cashing out these funds and laundering them abroad.

An important part of this process has been to “burn” banks with the assistance of the Deposit Insurance Agency. Under the control of the FSB, criminal financiers were able to launder money through small banks, whose licenses the central bank would then revoke. This, in turn, opened new opportunities for grifters—those in the FSB and their seedy associates—to profit by restructuring the banks’ assets or stealing funds allocated for their reorganizations.

Throughout the 2000s, the Federal Tax Service, the Federal Customs Service, and the central bank came under indirect SEB control when SEB officers were seconded to those agencies. This arrangement put large sums within easy reach of the seconded officers, and it’s primarily thanks to the SEB that corruption has become the norm for a significant part of the FSB. The competition for spoils among various groups in the SEB has led to public scandal and criminal cases.

Schemes of budget theft through tax refunds, cashing out, and money laundering.

Collaboration with the Deposit Insurance Agency

To understand how deeply the SEB and FSB are enmeshed in the shadow economy, consider the case of three Department K colonels arrested in April 2019: Kirill Cherkalin, then director of a branch of the department; Dmitry Frolov, deputy department chief until his dismissal in 2013; and Alexander Vasiliev.54

Formally, Department K’s purpose is to ensure the security of the Russian banking system, but the department’s far-reaching authority creates fertile ground for virtually unlimited criminal activity. Cherkalin and his colleagues extorted bribes, “protected” businesses, laundered money, seized and liquidated banks, and initiated custom-made criminal cases against targets of their own selection. During searches, FSB officers seized jewelry and cash worth 12 billion rubles (about one hundred and eighty million dollars at the time), but the accused were charged in only two cases of extortion and bribery: against Cherkalin over eight hundred and fifty thousand dollars and against Frolov and Vasiliev over 490 million rubles.55

Led by Frolov, they worked closely with the Deposit Insurance Agency, which sent intelligence reports—in effect, a financial “casing”—to Department K that allowed Frolov and then Cherkalin to choose new victims. Targets would be offered a “solution to their problems” in exchange for payoffs. Victims who refused would lose their banking licenses and have their assets transferred to people close to the FSB. Dossier Center sources indicate, however, that paying up did not always help: In some cases, even after receiving bribes, FSB officers, along with the DIA and the central bank, still liquidated the bank.

Immediately after the arrest of Cherkalin and his accomplices, a high-ranking DIA official, Valery Miroshnikov, left the country.56 According to Dossier Center sources, there is a direct causal link between Cherkalin’s arrest and Miroshnikov’s sudden flight. As this case shows, corruption, money laundering, and theft are a thoroughly institutionalized shadow industry that is lucrative for some, but for others carries the threat of bankruptcy, forced emigration, or criminal charges. Similarly, the prosecutors’ decision not to investigate multiple additional accusations against Cherkalin suggests that his trial and conviction were less about law and order and more about a power struggle within the security forces.57

A picture of complex bureaucratic policy becomes apparent, both formal and informal to those who execute it. The interests of representatives of four departments of the special services coincide

- That of Directorate “K” in the SEB, whose chief, Ivan Tkachev, initially sided with Shestun.58

- That of the Moscow regional FSB, which Shestun worked out on behalf of the governor of the Moscow region, Andrei Vorobyov.59

- That of Sixth Service of the USB/FSB, which officially carried out the state’s defense of Shestun (for which he, in his own words, paid “bribes.”).

- The “M” department (presumably), who was trying to take advantage of the current situation for his own apparatus interests.

The power of Igor Sechin’s special Sixth Service: The Sugrobov and Ulyukaev cases

One of Putin’s closest allies is Rosneft Chief Executive Officer Igor Sechin, whose relationship with the president goes back to the 1990s in St. Petersburg, where Sechin was a deputy of Putin’s.

Serving as deputy chief of the presidential administration in 2004 and 2005, Sechin was well-placed to create the Sixth Service within the FSB’s Internal Security Department (USB). The service enjoys considerable autonomy and often serves as an elite unit, executing the most delicate operations, such as the arrests of regional governors, on orders from the country’s leadership.60

Managers of the Sixth Service have almost always had access to the president and Sechin, bypassing the direct chiefs of the USB and the entire FSB. This special status gives officers of the Sixth Service ample opportunities to make a profit. According to aDossier Center anonymous sourcewith firsthand knowledge of the Sixth Service, referred to here as “S1,” employees of this unit funneled money out of targets associated with Russian Railways for a long time, extracting substantial commercial benefits from this.61

It was allegedly corruption involving Russian Railways and its director at the time, Vladimir Yakunin, that led to the downfall of Denis Sugrobov, then chief of the Interior Ministry’s anti-corruption unit. In Sugrobov’s case, mentioned earlier in this report, he and his deputy, Boris Kolesnikov, were arrested in 2014 and charged with abuse of power after allegedly enticing FSB officers to accept bribes. Sugrobov is now serving a twelve-year sentence and Kolesnikov is dead, having jumped or been pushed from a balcony at the headquarters of the Investigative Committee, Russia’s equivalent to the FBI. S1, the Dossier Center source, said Kolesnikov was thrown from the balcony by an operative of the Sixth Service.62

Evidence from the Sixth Service was used to arrest Sugrobov, who the source said was targeted because he had compromising materials on officers of the Sixth Service. The operation against Sugrobov was led by Oleg Feoktistov, who at the time was the deputy head of the FSB’s Internal Security Department and was also instrumental in another high-profile case, which had Sechin’s fingerprints all over it.

Before a 2016 meeting of the Anti-Corruption Council. Left to right: Chairman of the Investigative Committee Alexander Bastrykin, Director of the Federal Security Service Alexander Bortnikov and Minister of Economic Development Alexei Ulyukayev. Credit: Office of the President of Russia

In November 2016, Economic Development Minister Alexei Ulyukaev was arrested and accused of taking a $2 million bribe to drop his opposition to state-owned oil company Rosneft’s takeover of Bashneft, a private oil producer.63 Sechin is chief executive of Rosneft, where at the time of Ulyukaev’s arrest, Feoktistov was head of security, having recently left the Sixth Service. Feoktistov was joined in the Ulyukaev operation by Ivan Tkachev, another alumnus of the Sixth Service who was now leading Department K.

Ulyukaev protested his innocence, saying that he had merely accepted a Christmas gift basket, not a bribe, from Sechin.64 Typically in such politicized criminal cases, the events outlined in the indictment are just a pretext for prosecution, which is really prompted by personal or commercial conflicts. According to S1, however, Ulyukaev’s case is the rare because the stated reason for prosecution is not a fable.65 The minister was eventually sentenced to eight years in prison.66

The Ulyukaev case is an excellent example of how former and current FSB officers act as an instrument of interclan struggle. It also clearly demonstrates how members of Putin’s inner circle use special services for their own purposes—in particular, to build their parallel power structures and to lure security officers into them. Sechin, apparently due to his excessive ambitions, attracted the discontent of the First Person (Putin), and Feoktistov lost his job both in a high position at Rosneft and the FSB.67 This took away a proven tool in Sechin’s arsenal, Fektistov, and served as a shot across the bow—remember who is in charge.

FSB surveillance of other security forces

Department M provides counterintelligence support for law enforcement agencies. It is the police of the police, exercising informal oversight over the police, investigators, prosecutors, and the courts. The department plays a role in the appointments of all significant posts in these departments and monitors their employees. This arrangement allows the FSB to keep the rest of the security forces in check: emshchiki—officers of the directorate—can arrange the appointment of their own people, filter out undesirable candidates, or demand “thanks” and cooperation from security officers already appointed. As has been reported widely in the press, Department M also exercises informal control over judges and may influence their decision-making, although on paper the judicial system is independent.

Department M’s oversight of law enforcement bodies gives its corruption a wide scope: Its managers can run schemes not only through their department but also via employees of other agencies. Department M management has played an essential role in the shadow financial services market since at least the mid-2000s. It’s likely that the market has been divided among the three divisions of the FSB, which, at times competing and at times cooperating with one another, have facilitated the laundering and transfer of hundreds of billions of rubles abroad. At the same time, law enforcement agencies, which Department M is called to monitor, are regularly rocked by corruption scandals, some of which involve emshchiki themselves.

Department M, like the entire FSB, seeks to subordinate the rest of the security structures to its will. Often its operatives pursue this aim by bringing criminal cases against high-profile defendants, effectively decapitating law enforcement agencies and installing their own loyalists. These operations, among other things, send a signal about the place of the FSB atop the security hierarchy.

In 2015, a long-running conflict between the FSB and the Investigative Committee came to a head. The committee had been an independent body for only five years, having been split off from the Prosecutor General’s Office in 2011. But it had become an indispensable tool, including for putting pressure on businesspeople and dissenters. By that time, the Prosecutor General’s Office had lost its authority to initiate criminal cases and the law limited the conditions under which the FSB could initiate investigations. To expand its influence, the FSB would need to put the Investigative Committee under its control.

A shootout in a Korean restaurant in Moscow provided the FSB’s opportunity.68 Two people were killed when a crime boss and his goons attempted to extort money from the restaurant owner and a brawl ensued, which ended in shots fired. Investigators at the Investigative Committee, who may have had links to the crime boss, slow-walked the case and reduced the charges. Accused of corruption in the case were Mikhail Maksimenko, chief of the Investigative Committee’s Internal Security Directorate (not to be confused with the FSB department of the same name); his deputy, Alexander Lamonov; and three top investigators in Moscow.69

A decisive blow came the next year, when the influential director of the Investigative Committee for the Volgograd Region, Mikhail Muzraev, was arrested along with other high-ranking officers.70 Muzraev, a veteran investigator, had trained several generations of officials and was expected to lead the entire Investigative Committee. Unlike the conflict between the Interior Ministry and the FSB that led to the Sugrobov case, Muzraev’s arrest and the subsequent filling of important posts with FSB loyalists helped to informally subordinate the Investigative Committee staff.

Department M itself has been buffeted by internecine strife. For example, when Sergei Alpatov took over the management of the department in 2014, he sought to clear out those who were loyal to his predecessor, Viktor Kryuchkov. Alpatov launched an operation that nabbed Dmitry Zakharchenko, leader of the Interior Ministry’s anti-corruption unit, as well as other employees of the ministry and of the FSB, including in Alpatov’s own department.

Investigators found 13 apartments and 14 parking spaces in exclusive areas of Moscow, four cars, a 500-gram gold bar, Rolex watches, jewels, and currency worth nine billion rubles belonging to Zakharchenko and his family.71

The group had enjoyed the protection of Kryuchkov for more than a decade as they and the police officers they oversaw “resolved issues” for businesses in the gray economy and provided illicit services to high-ranking officials.72 Among the sources of the huge wealth they had accumulated was likely kickbacks and embezzlement on state contracts with Russian Railways.

People walk across Red Square during first snow in Moscow October 14, 2007. Seen in the background are St. Basil’s Cathedral and the Kremlin. Credit: Reuters

Conclusion

The story of Russian intelligence, the KGB, and FSB over the past thirty years is extraordinary. From a period of great weakness and disorganization in the first years after the fall of the Soviet Union, the FSB has become the defining and governing institution in Putin’s Russia.

In the most repressive period of Soviet and even Russian history, Stalin held the NKVD (the KGB’s predecessor) firmly in his grasp. Today, the FSB is more than an instrument of Putin. His KGB background has had a great deal to do with the rise of the FSB, many of his close associates have come from the KGB ranks, and the FSB is his preferred tool for getting things done in Russia. To that end, Putin has installed these KGB/FSB associates in key government and commercial positions, extending the FSB’s reach well beyond the spheres where Stalin’s secret police held sway.

But while it is authoritarian, Putin’s Russia is a more free-wheeling place than the Soviet Union, and the president’s control over the FSB does not rival Stalin’s control of the NKVD or even the Soviet Politburo’s control over the KGB. Senior FSB officials and even lower-ranking officers can pursue their own plans and ambitions. The abuses and corruption at the top of the FSB are mirrored further down, as more junior officials set up their own extortion and protection rackets to bleed the country’s businesses. And as different parts of the FSB seek their own economic advantage, they start to compete with each other, adding another complication to doing business in Russia—something that could, over time, chip away at the stability of the Putin regime.

Acknowledgements

The Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center would like to recognize the masterful reporting of the Dossier Center, and thank the Future of Russia Foundation for its generous support in bringing this work to an English-speaking audience. The Eurasia Center would also like to recognize the contributions of Michael Newton, Barbara Frye, Doug Klain, Adrian Hoefer, Sabrina Hernandez, Laryssa Horodysky, Andrew D’Anieri, Uri Friedman, Susan Cavan, and Becca Hunziker.

The original article can be found @AtlanticCouncil

Leave a Reply