The head of NATO’s Innovation Unit looks at how the Allies need to leverage comparative advantage, creativity and capital to win the race to adopt emerging disruptive technologies.

Dwight Eisenhower, NATO’s first Supreme Allied Commander Europe and later the 34th President of the United States, argued for the “most defense at less cost with least delay”. He believed that the real challenge was to “build this defense with wisdom and efficiency. […] We must achieve both security and solvency. In fact, the foundation of military strength is economic strength.” (Congressional Records, 1962) These statements were made against the backdrop of an existential arms race with the Soviet Union and the bipolar world of the Cold War. Through America’s net assessment strategy(comparing two systems together and seeking opportunities/risks), capitalism and competitive spending – underpinned by liberal democratic values – the West used these tools to beat the Soviets. It worked and that was the “end of history”. Maybe not.

Today, NATO’s competition is a global one and the race is one of technological adoption – that is, the acceptance, integration and use of new technology in society. From artificial intelligence to quantum and everything in between, governments are in a race to leverage these technologies at scale and speed – first adopter advantage for emerging disruptive tech could not be more prevalent in the world of geopolitics and deterrence. Indeed, the nations that win this race may be those with the most agile bureaucracy rather those with the best technology.

From artificial intelligence to quantum and everything in between, governments are in a race to leverage these technologies at scale and speed

In contrast to the Cold War, the United States and its NATO Allies are unlikely to simply outspend others. In a post-Covid-19 world, rebalancing public finances could see further financial pressure placed on Allied defence budgets. We now need a different advantage, one which will deliver in the short term and build resilience over the longer term – more defence at less cost with least delay. This starts with our people, their creativity, education and access to funding. It ends with a robust pipeline of new dual-use (civil and military) technologies constantly being created, commercialised and capitalised upon.

The Alliance’s transatlantic nature places it in a unique position within the international order to provide both demand-side policies and supply-side resources that can genuinely build such a pipeline, creating not only innovations but entirely new markets – as Eisenhower noted: the foundation of military strength is economic strength. Recent history would suggest, the model of democracy and Allied governments’ willingness to make big bets on mission-oriented technology does indeed create new markets and it is this model, underpinned by shared values, which will be key to NATO’s longer term success.

But what about now? In the short term, NATO innovation needs to lay the foundations for Allies to realise those benefits of an Alliance-wide approach. Answers may lay in focussing on two core areas:

- addressing the fragmentation of researchers, academia, start-ups and government at the beginning of this pipeline – that is, managing uncertainty.

- being able to adopt and scale these new technologies as and when they are ready – meaning the necessity of nimble, agile investment and acquisition entities across both public and private sectors, all of which need to be equally incentivised to take significant levels of risk.

These activities are difficult in their own right but combining them into an Alliance innovation pipeline, while attempting to make use of the comparative advantage each Ally brings to the table, leaves the Alliance with a “wicked problem”. It is wicked because it demands a combination of both sustained and disruptive innovation (which seeks to radically change the status-quo) occurring simultaneously across NATO.

Leveraging diversity

In aggregate, the Alliance has an abundance of world-class academic institutions, the finest scientific researchers, amazingly creative start-ups and a mature well-resourced financial eco-system. These constitute the core ingredients, which, when combined and focused, can solve dual-use, ‘tough-tech’ problems – that is, challenges facing both defence and non-defence sectors, such as augmented reality and quantum computing.

A dual-use model is important for disruptive defence innovation because when we eventually get to commercialising such tough-tech breakthroughs, Allies will need start-ups and tech firms to maximise the reach of their products by looking at ‘total addressable problems’ rather than ‘total addressable markets’. In other words, we should not want start-ups building the next wave of technology to have governments as their only customer. We want such technologies to benefit society too and therefore have civil, commercial use. Such commercial use then drives the subsequent development of said technology, pulling the government-side along with it, which means better products and technology all round – building defence with wisdom and efficiency.

Indeed, dual-use potential will help align the incentives of our researchers, entrepreneurs and finance communities as the prospective commercial upside (problem) will be big enough for them to undertake the investment of commercialisation. The geopolitical advantage such disruptive innovation fosters (picking winners via big bets on the next breakthrough) will also be large enough to allow for its creation via early stage patient public sector capital investment.

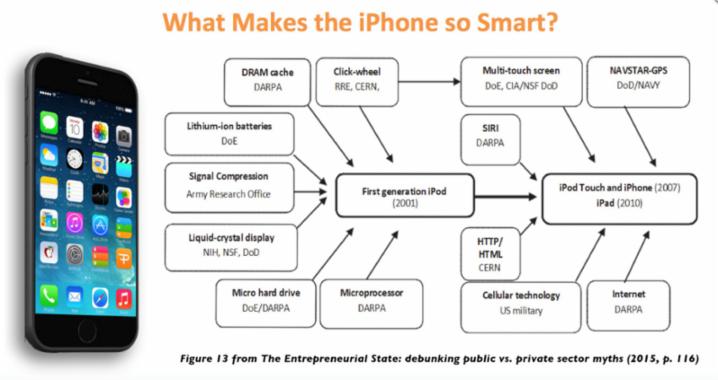

But before we get to commercialisation, we need to create the direction of what it is we wish to see commercialised. Technological disruptive innovation does not just happen. It starts with a mission-oriented vision, where measuring risk is impossible and only uncertainty reigns. It requires bold moves that will signpost the future; the confidence to place big bets on technology not yet invented; and an ability to pick winners – all of which must be underpinned by persistent engagement, encouragement and enlightenment. Since the end of the Second World War, only one entity has taken-on such uncertainty: Allied governments (see image below).

Technological disruptive innovation does not just happen. It starts with a mission-oriented vision, where measuring risk is impossible and only uncertainty reigns.

Step 1: agree innovation priorities among Allies

The first step towards fixing the fragmentation of Allied disruptive innovation is for Allies, through the NATO framework, to focus on agreed innovation priorities. This will allow them to pick winners and invest public patient capital – the private sector is unlikely to invest venture capital as the risk is simply too high (nations tend not to go out of business and can take on such uncertainty). This direction and investment will help to maintain NATO’s overarching technological edge. Indeed, as Keynes and Weber argued, the ability to make things happen that otherwise would not needs a combination of technological, policy and bureaucratic skills matched by investment.

Step 2: leverage the comparative advantage of the Alliance

If Allies are to achieve most defence at less cost with least delay built with wisdom and efficiency, then it is logical to leverage those natural advantages that geography and skill sets afford NATO member states. A network of the finest universities across the Alliance should be established and resourced to allow cutting-edge multinational research to take place across multiple disruptive technologies simultaneously. Perhaps Stanford could lead on relevant AI research, while Delft and the University of Chicago partner on quantum; maybe Imperial College London looks at biotechnologies with Johns Hopkins University, while Tallinn University centres its efforts on next generation cyber defences; and the École Polytechnique and Massachusetts Institute of Technology examine future telecommunication needs.

The point is Allies will need to leverage such networks of universities in conjunction with national government research labs to provide maximum innovation coherence. The diversity of multinational, multi-disciplined defence and security innovation research teams, which NATO can engender, is a huge asset and is the Alliance’s competitive advantage.

So to fix the fragmentation at the beginning of our innovation pipeline, we need to have clear mission-oriented Allied direction on where to focus resources for disruptive innovation research, maximising comparative advantage across our geography(s) and linking up universities with government research entities. All of this could be funded by Allies through public sector early stage patient capital.

As the image above shows, governments have done this before and the technologies created (internet, GPS, touchscreen et al, which fed into the building of the iPod and iPhone) have had a huge impact on the way we live. However, for all those successes, there will have been many failures and this is where Allies will need to get comfortable. To quote one anonymous Allied defence innovator: “if our success rate begins to go above 35 per cent, I start to worry. It means we’ve stopped taking big enough risks.” Indeed, obvious research areas Allies might collaborate on include the follow-on to 5G or the technology needed to enable total supply chain assurance, for example.

Utilise, adopt and scale

Where the first stage of NATO’s innovation pipeline should centre on the creation of disruptive innovative technologies, stage two is all about their utilisation and adoption at scale.

Utilisation

This is where initial public venture capital (VC) entities, such as in-q-tel, NSSIF, DefInvest and SmartCap, can help ‘crowd in’ trusted private venture capital to provide safe financing to NATO’s fledgling start-ups, thereby minimising their susceptibility to nefarious foreign direct investment. This issue is impacting many start-ups as they raise funds and carries implications when they wish to export their products but may not be able to, due to unfriendly foreign ownership and technology transfer concerns raised by Allied governments.

In addition to Venture Capital entities supporting the trusted financing of Allied start-ups, innovation accelerators – in combination with elite universities, and supported by Allied defence professionals (operators, investors and procurement experts) – can help provide the necessary ‘polish’ to start-ups and their value propositions. This will create the necessary ecosystem to maximise the likelihood of commercial success. The United States’ Air Force Ventures is an interesting model of this approach, which helps to acquire new start-up products at speed without being bogged down by acquisition bureaucracy.

Adoption

But even when dual-use disruptive innovation is commercialised, turned into prototypes and the product/market fit is achieved, the challenge of getting initial contracts from customers (both government and commercial) remains. Cash is king for young companies, as they do not have the financial reserves to work through long acquisition processes often associated with Allied governments. If start-ups cannot close deals in a matter of weeks and months rather than quarters and years, then they would not attempt to (opportunity cost).

Now, some commentators may argue: Why spend so much time discussing start-ups? Traditional large armaments companies can be innovative. Why go through all this effort for tiny companies that may or may not make it?

The reason is simple: the competition and creativity generated by start-ups is good for the Allied defence ecosystem. Allied open democracies and open educational models bring about levels of creativity which other forms of government are unable to do. This maximises disruptive innovation efforts and, as such, forces incumbents (large companies) to compete with new, fresh thinking – it builds resilience.

Such creativity and disruption is NATO’s competitive advantage. Therefore, NATO needs to adapt its acquisition models to accommodate start-ups, their timelines and their potential. This fundamentally means our acquisition professionals should be empowered to take measurable risk. As one Ally’s legislative body recently remarked: “Defence stakeholders must integrate the risk culture, which is the only way to both enable innovation in defence and to very quickly capture dual or civilian innovation. Acculturation to innovation is a priority.”

Scaling

If we have managed to commercialise new technology, adopt it quickly as a prototype and now wish to scale, how might this be done? Big tech could have a role to play here. In May, it was reported that, in the first quarter of 2020, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet and Microsoft spent over 29 billion US dollars on research and development (R&D). That is more than the entire 2020 NASA budget and represents a 17 per cent increase on the same time period last year.

In November 2018, the US Congressional Research Service noted: “In 1960, the United States accounted for 69% of global R&D, with U.S. defense-related R&D alone accounting for more than one-third of global R&D (36%). Additionally, the federal government funded approximately twice as much R&D as U.S. business. However, from 1960 to 2016, the U.S. share of global R&D fell to 28%, and the federal government’s share of total U.S. R&D fell from 65% to 24%, while business’s share more than doubled from 33% to 67%. As a result of these global, national, and federal trends, federal defense R&D’s share of total global R&D fell to 3.7% in 2016.”

Big tech has the resources and wherewithal to be able to scale new technologies at speed. They could partner with successful start-ups, perhaps through a joint venture or an Alliance-wide public-private partnership, to provide those scale-up skills that start-ups lack (for example, compliance, legal support, production on mass, intellectual property protection) without necessarily acquiring these young companies.

Sceptics will say this would present big tech with too many opportunities for mergers and acquisitions and thus create monopolistic risk. They might be right and clearly incentives for all parties would need to be found. But, if we are to win the technological adoption race built upon liberal democratic values, we need to use every advantage we have.

To utilise, adopt and scale these technologies effectively, we must have at the forefront of our minds the need to work at the speed of relevance rather than the speed of approval. This means new ways of financing technologies, interacting with tech firms both big and small, and much more agile acquisition models, which carry the empowerment and incentives to those responsible for equipping the Alliance. Such a cultural shift will not be easy – but innovation rarely is.

As we look towards NATO 2030 and heed Eisenhower’s words of achieving both security and solvency, while noting that the foundation of military strength is economic strength, a resilient innovation pipeline that leverages our comparative advantage, creativity and capital will be critical to the Alliance maintaining its technological edge built on shared Allied values.

Leave a Reply